History is often viewed as a linear progression of successful inventions, yet the digital landscape is littered with “ghost” technologies—innovations that were technically viable but failed due to timing, corporate hesitation, or lack of infrastructure. These near-misses represent alternate timelines where the internet, mobile computing, and consumer electronics could have evolved in entirely different directions. Analyzing these failures provides insight into the fragile nature of innovation and the external factors that dictate which ideas survive the transition from prototype to household name.

Table of Contents

ToggleArchitectural Analysis: The Pre-Digital Prototypes

Before the silicon revolution, several mechanical and analog attempts at modern digital concepts nearly redefined information accessibility. These devices were often decades ahead of the supporting hardware required to make them ubiquitous.

The Fiske Reading Machine (1922)

Long before the Kindle or iPad, Rear Admiral Bradley Fiske patented a “reading machine” designed to abolish bulky volumes. Using a sophisticated lens system to read microscopic text on condensed cards, the device folded into the size of a fountain pen. Had the publishing industry pivoted toward this format, the history of literacy and data storage might have prioritized optical magnification over electronic scanning for most of the 20th century.

The 1964 Picturephone

Bell Labs debuted the Mod I Picturephone at the New York World’s Fair, conceptualizing video conferencing half a century before the rise of Zoom. While the technology functioned, the exorbitant cost and the requirement for a dedicated high-bandwidth network—which AT&T struggled to implement at scale—relegated the device to a historical curiosity. This near-miss delayed the normalization of video-first communication by several generations.

The Psychology of Risk in Digital Evolution

The failure of a technology is rarely just a technical issue; it is often a failure of risk management or strategic foresight. In the late 20th century, many giants of the industry, such as Xerox and Kodak, held the keys to the future but were too risk-averse to unlock the doors. They viewed their existing monopolies as permanent, failing to realize that the digital world favors those who gamble on disruption.

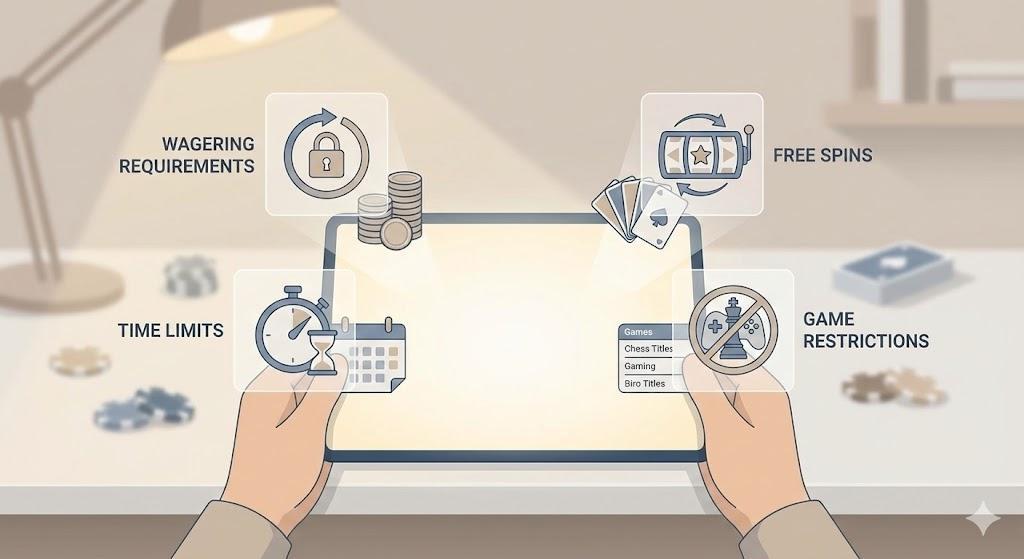

This intersection of high-stakes decision-making and digital precision is a common thread in modern technical entertainment. For instance, the VulkanVegas platform operates on a foundation of calculated risk and sophisticated software architecture, mirroring the same competitive environment where tech pioneers once fought for dominance. Just as an early tech company had to weigh the odds of adopting a new protocol like Ethernet over Token Ring, modern digital platforms must constantly balance user engagement with architectural stability to remain relevant in a crowded market.

Lost Standards and the “Supernova” Scenarios

Beyond hardware, the software and networking protocols that didn’t become the standard offer a fascinating look at what could have been.

The Open-Architecture Networking Rivalry

In the 1970s, the path toward the modern internet was not guaranteed. While ARPANET’s packet-switching eventually won out, several competing European projects, such as the UK’s NPL network, proposed different methods of federating independent networks. A shift in funding or a different geopolitical climate could have resulted in a fragmented “splinternet” much earlier than the current era of regional firewalls.

The Apple Newton and the PDA Gap

The Apple Newton (1993) is frequently cited as a failure, yet it contained the DNA of the modern smartphone. Its primary “miss” was its handwriting recognition software, which became the subject of public derision. Had Apple perfected the algorithm in 1993 rather than 2007, the mobile revolution might have occurred during the dial-up era, creating a mobile web experience based on text-heavy protocols rather than the media-rich environment we inhabit today.

Comparative Evaluation of Technological Turning Points

To understand why some technologies succeeded while others became footnotes, one must examine the variables of cost, infrastructure, and consumer readiness.

| Innovation | Concept Date | Modern Equivalent | Primary Failure Catalyst |

| Pigeon Cameras | 1908 | Satellite/Drone Imagery | Mechanical timing limitations |

| Sloot Coding System | 1995 | Advanced Compression | Developer’s sudden death (lost source) |

| Microsoft SPOT | 2004 | Apple Watch/Smartwatches | Reliance on FM radio data delivery |

| WebTV | 1996 | Smart TVs/Streaming | Latency of dial-up infrastructure |

The takeaway from these historical “glitches” is that technical superiority does not guarantee survival. The Sloot Coding System, for example, allegedly allowed a full-length film to be stored in just 8 kilobytes of data. When the inventor died without sharing the final algorithm, a potential revolution in data storage and streaming vanished instantly. These events remind us that the digital world we know is just one of many possible outcomes, shaped as much by chance as by engineering.

Beyond the Success Narrative

The digital world is often presented as a triumph of the most efficient systems, but a closer look at tech history reveals a landscape shaped by narrow escapes and forgotten geniuses. When we reflect on these near-misses, it becomes clear that “innovation” is a fragile state. The difference between a global standard and a forgotten patent is often nothing more than a few months of funding or a single executive’s decision. As we move into an era of AI and quantum computing, the lesson remains: the next world-changing technology might already exist, currently gathering dust as a “failed” prototype.